Ever spotted a big, white bird and thought, “Is that a swan, an egret, or just a really fancy pigeon?” You’re not alone. White birds are some of the most eye-catching creatures in the wild, whether they’re soaring through the sky, wading through wetlands, or casually judging your beach picnic. From the majestic great egret to the adorably awkward American white pelican, these birds are as diverse as they are beautiful.

In this guide, we’ll take a closer look at the most common white birds, where to find them, and what makes them so unique. Whether you’re a birdwatching enthusiast or just someone who keeps mistaking an ibis for a seagull (don’t worry, it happens), you’re in the right place. Let’s dive into the world of nature’s most angelic-looking—and sometimes surprisingly mischievous—feathered friends!

Great Egret

- Scientific Name: Ardea alba

- Size: 37–41 inches (94–104 cm) tall, with a wingspan of up to 67 inches (170 cm)

- Weight: 1.5–3.3 lbs (700–1,500 g)

- Nesting Season: March to July (varies by region)

- Range: North and South America, found in wetlands, swamps, and coastal areas

The great egret is one of the most striking white birds in North America, known for its tall, slender build and graceful movements. Often seen wading through shallow waters in search of fish, these birds are expert hunters, using their long, sharp bills to spear their prey with precision.

During the breeding season, great egrets transform into something even more spectacular. They grow delicate, wispy plumes called “aigrettes” on their backs, which were once so prized in the fashion industry that the species nearly went extinct due to overhunting. Thankfully, conservation efforts have helped their populations recover, and today, they are a common sight in wetlands across the continent.

These birds can be quite aggressive over food, especially if they’ve gotten used to humans. As a small child, I had one snatch a fish out of my hand while fishing!

Immature Little Blue Heron

- Scientific Name: Egretta caerulea

- Size: 22–29 inches (56–74 cm) tall, with a wingspan of about 39–41 inches (99–104 cm)

- Weight: 10–14 oz (275–400 g)

- Nesting Season: March to July (varies by region)

- Range: Southeastern U.S., Gulf Coast, Central and South America, in wetlands, marshes, and coastal areas

If you ever spot a small, pure-white heron standing among a group of snowy egrets, don’t be fooled—this bird may not be what it seems! Immature little blue herons are completely white for their first year of life before they gradually transition into the slate-blue plumage of adulthood. This color change often results in a patchy, mottled look during their “awkward teenage phase,” making them one of the easiest herons to misidentify.

Scientists believe that this white phase helps young little blue herons blend in with flocks of snowy egrets, which may offer protection from predators. It also makes it easier for them to catch prey, as fish and other aquatic creatures are less wary of white birds, which are more common in their environment.

Despite their ghostly white appearance in youth, little blue herons behave much like their darker adult counterparts. They wade slowly through shallow waters, patiently waiting to strike at fish, frogs, and crustaceans. Unlike some other heron species, they prefer to hunt alone rather than in groups.

American Pelican

- Scientific Name: Pelecanus erythrorhynchos

- Size: 50–70 inches (127–178 cm) tall, with a wingspan of up to 9 feet (275 cm)

- Weight: 10–20 lbs (4.5–9 kg)

- Nesting Season: April to June

- Range: North America, breeding in inland lakes and marshes in the north and wintering along the southern coasts

The American white pelican is one of the largest birds in North America, with a wingspan that rivals some of the biggest raptors.

Instead of dramatic plunge-diving like brown pelicans, American white pelicans use teamwork to corral fish into shallow areas before scooping them up with their signature bright orange bills. Their expandable throat pouches can hold up to three gallons of water, making them highly efficient hunters.

These birds are surprisingly gigantic!

In the winter months, you can find these big birds in Florida and along the Gulf Coast. I’ve seen them everywhere from Everglades National Park to Lousiana State University’s campus. In the summer, they head north to breed in inland lakes (including in Jackson Hole, Wyoming!)

During the breeding season, these pelicans develop a unique, comical-looking knob on their upper bill, which falls off after mating. They nest in large colonies on isolated islands, where both parents take turns incubating their eggs and feeding their young.

Snowy Egret

- Scientific Name: Egretta thula

- Size: 22–26 inches (56–66 cm) tall, with a wingspan of about 39 inches (99 cm)

- Weight: 12–19 oz (350–550 g)

- Nesting Season: March to July (varies by region)

- Range: North, Central, and South America, found in wetlands, marshes, and coastal areas

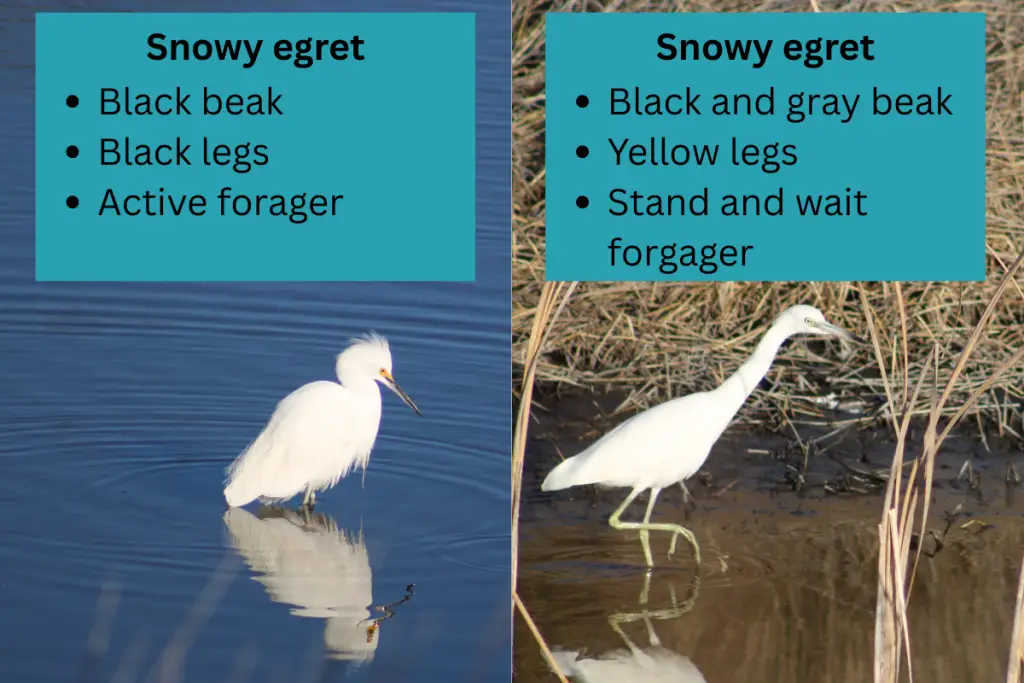

The snowy egret have pure white plumage, thin black bill, long black legs, and bright yellow feet, which makes it stands out among wading birds. During the breeding season, snowy egrets take their beauty up a notch, growing delicate, wispy plumes on their backs and heads—once so coveted by the fashion industry that these birds nearly disappeared due to overhunting in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Luckily, the population rebounded. But it’s scary to think that we almost wiped out these beautiful birds in pursuit of hats!

Unlike some of its more patient relatives, the snowy egret is an active and animated hunter. It darts, dashes, and even dances through shallow waters, using its bright yellow feet to stir up fish and other small prey. The action seems to work well for this bird, and creates quite the show.

Snowy egrets nest in large colonies, often alongside other herons and egrets, building stick nests in trees or shrubs near water. Both parents take turns incubating the eggs and feeding their chicks, who quickly learn that patience is not a snowy egret’s strong suit.

Wood Stork

- Scientific Name: Mycteria americana

- Size: 33–45 inches (85–115 cm) tall, with a wingspan of up to 5.5 feet (140 cm)

- Weight: 4–6.5 lbs (1.8–3 kg)

- Nesting Season: December to June (varies by region)

- Range: Southeastern U.S., Central and South America, in freshwater and coastal wetlands

The wood stork is one of the most unusual-looking white birds in North America. While its long legs, massive wings, and white plumage give it an elegant silhouette, its bald, scaly black head makes it look more like a prehistoric relic than a graceful wader. Despite its somewhat awkward appearance, the wood stork is an impressive bird, it rebounded from near-extinction.

Unlike egrets and herons that hunt by sight, wood storks use a tactile hunting method, snapping their bills shut in just 0.025 seconds when they detect fish, frogs, or crustaceans in the water. This “strike reflex” makes them one of the fastest-feeding wading birds in the world.

Wood storks are colonial nesters, forming large breeding colonies in cypress swamps and mangroves. Their nesting success depends heavily on water levels—they thrive in years with just the right balance of rainfall and drying periods, which concentrate fish for easy feeding. If food is scarce, they may abandon their nests, making them particularly vulnerable to habitat changes.

Once considered endangered due to wetland drainage and habitat loss, wood stork populations have made a comeback thanks to conservation efforts.

White Ibis

- Scientific Name: Eudocimus albus

- Size: 21–27 inches (53–68 cm) tall, with a wingspan of about 35–41 inches (89–105 cm)

- Weight: 1.5–2.3 lbs (700–1,050 g)

- Nesting Season: March to September (varies by region)

- Range: Southeastern U.S., Gulf Coast, Central and South America, in wetlands, coastal marshes, and urban parks

The white ibis has pure white feathers, bright red legs, and long, curved bill. Found in wetlands, marshes, and even suburban neighborhoods, these sociable birds are often seen in flocks, foraging for food in shallow water or probing through soft mud with their distinctive beaks.

Unlike other wading birds that rely on sight, white ibises hunt by touch, sweeping their bills back and forth in the water to locate small crustaceans, insects, and fish. Their diet has an interesting side effect—the more shrimp they eat, the redder their legs and faces become!

White ibises are highly adaptable, often seen in urban parks, golf courses, and even parking lots where they casually strut around looking for snacks. I grew up watching them chow down on the bugs in my front yard in Hollywood, Florida.

During nesting season, they form large colonies in trees near water, with both parents sharing the responsibility of incubating eggs and feeding their young.

Snow Goose

- Scientific Name: Anser caerulescens

- Size: 25–31 inches (64–79 cm) tall, with a wingspan of about 53–65 inches (135–165 cm)

- Weight: 5–9 lbs (2.3–4.1 kg)

- Nesting Season: May to August

- Range: Breeds in the Arctic tundra; migrates to the U.S. and Mexico for the winter, favoring wetlands, grasslands, and agricultural fields

The snow goose is a medium-to-large geese known for their pure white feathers, contrasting black wingtips, and bright pink bills and legs. However, not all snow geese are actually white—some belong to a darker “blue morph” variation, which sports a mix of gray and white feathers. Despite their color differences, both morphs are the same species and often intermingle in large flocks.

Snow geese are extremely vocal, filling the skies with their loud, honking calls as they migrate in massive V-shaped formations. Their migrations are some of the most spectacular natural events in North America, with hundreds of thousands of birds moving between their Arctic breeding grounds and their wintering areas in the southern U.S. and Mexico.

During nesting season, snow geese return to the remote Arctic tundra, where they build shallow nests on the ground. The goslings are born ready to go, leaving the nest within 24 hours and quickly learning to forage alongside their parents.

Cattle Egret

- Scientific Name: Bubulcus ibis

- Size: 18–22 inches (46–56 cm) tall, with a wingspan of about 39 inches (99 cm)

- Weight: 8–14 oz (230–400 g)

- Nesting Season: May to August (varies by region)

- Range: North, Central, and South America, found in wetlands, agricultural fields, and pastures

Cattle egrets are often seen perched on cows, horses, or even bison. These tiny white herons love to follow grazing animals, picking up insects and other small creatures that are stirred up by the movement of the animals. It’s not uncommon to spot these egrets riding along with cattle as they roam through pastures, making them one of nature’s most unlikely team-ups.

Cattle egrets are highly adaptable and have spread rapidly throughout North America since they arrived by flight in the mid-1900s. Originally from Africa and Asia, they’ve now become a common sight in pastoral landscapes, agricultural fields, and wetlands. Their relationship with livestock is mutually beneficial, as they help keep animals free from pests, while also enjoying an easy meal.

During nesting season, cattle egrets form colonies that often include other wading bird species. They typically nest in trees or shrubs near water, building simple stick nests. Both parents share the duties of incubating eggs and caring for their young. Once the chicks are born, they are quick to learn the ropes of foraging alongside their parents.

Trumpeter Swan

- Scientific Name: Cygnus buccinator

- Size: 54–62 inches (137–157 cm) long, with a wingspan of about 79–90 inches (200–230 cm)

- Weight: 20–30 lbs (9–13.6 kg)

- Nesting Season: April to June

- Range: North America, primarily in the northern U.S. and Canada, with wintering areas in the Pacific Northwest, Great Lakes, and parts of the Midwest

The trumpeter swan is the largest native swan in North America, and it truly lives up to its name. With a wingspan that can stretch nearly 8 feet and its graceful, all-white plumage, this majestic bird is a symbol of beauty and strength in North America’s wetlands and lakes. Known for its deep, resonating calls that sound like a trumpet (hence the name), the trumpeter swan has earned a special place in both folklore and conservation efforts.

Trumpeter swans are also famous for their dramatic migrations, flying in V-shaped formations over long distances from their breeding grounds in the northern U.S. and Canada to their wintering areas in the southern U.S.

During the breeding season, trumpeter swans build large nests made of reeds and grasses on secluded lakes and ponds, usually away from predators. Their monogamous nature means that once they form a bond, they typically stay with their mate for life. Both parents share in the responsibilities of incubating eggs and caring for their cygnets, ensuring the young are well-fed and protected.

Once near extinction in the early 20th century due to habitat loss and hunting, trumpeter swan populations have recovered through dedicated conservation efforts.

Whooping Crane

- Scientific Name: Grus americana

- Size: 55–60 inches (140–152 cm) tall, with a wingspan of about 7.5 feet (230 cm)

- Weight: 10–15 lbs (4.5–6.8 kg)

- Nesting Season: April to June

- Range: Breeds in Canada and the northern U.S., migrates to the southern U.S. (primarily Texas and New Mexico) for winter

The whooping crane is a true icon of North America’s wetlands, known for its towering height, striking white plumage, and bold black wingtips. As the tallest bird in North America, it is impossible to miss, whether it’s soaring over marshes or performing its elegant courtship dance during the breeding season. Their trumpet-like calls (which sound like a loud “whoop”) give them their name and can be heard over long distances.

Once on the brink of extinction due to hunting and habitat destruction, the whooping crane’s population has made a remarkable recovery, thanks to years of dedicated conservation efforts. Today, this species remains endangered but has shown signs of recovery through active protection and breeding programs. These cranes are monogamous, forming lifelong pairs and nesting in isolated wetlands far from human activity.

During the breeding season, they create nests on the ground, typically in marshes or shallow ponds. The female lays one or two eggs, and both parents take turns incubating them. Once the chicks hatch, the parents provide constant care, teaching the young cranes to forage and protecting them from predators.

In the wild, whooping cranes migrate over vast distances from their breeding grounds in the northern U.S. and Canada to wintering areas in Texas, New Mexico, and Mexico.

Despite their recovery efforts, the whooping crane still faces threats from habitat loss, human activity, and climate change. However, efforts to protect and preserve their wetlands and migratory routes continue, offering hope for the survival of this remarkable bird.

Snowy Owl

- Scientific Name: Bubo scandiacus

- Size: 20–28 inches (50–71 cm) tall, with a wingspan of about 54–66 inches (137–168 cm)

- Weight: 3–4.5 lbs (1.4–2 kg)

- Nesting Season: April to June

- Range: Arctic regions of North America, with migrations to the northern U.S. during winter

The snowy owl is a stunning, ghostly bird that brings a touch of the Arctic wilderness to North America’s winter landscape. Known for its bright white feathers, sharp yellow eyes, and powerful wings, the snowy owl is one of the most iconic and striking birds in North America. These owls are typically found in the tundra and boreal forests of the far north, but during the winter months, they migrate southward in search of food, sometimes appearing in open fields or even near urban areas.

Unlike most owls, snowy owls are active during the day, hunting for small mammals, particularly lemmings, which make up a large portion of their diet. These silent hunters use their keen vision to spot prey from a distance, swooping down with grace and power to catch it. They are known for their ability to adapt to changing conditions, which is crucial as they face the challenges of the harsh Arctic environment.

While snowy owls are typically associated with the Arctic, they are migratory, and some may travel as far south as the northern U.S. during winter. Their migration is often linked to the availability of food, particularly when lemming populations fluctuate. During irruption years, when food is scarce in the Arctic, large numbers of snowy owls will migrate farther south than usual, becoming a rare and exciting sight for birdwatchers.

Though not endangered, snowy owl populations are facing threats due to habitat loss, climate change, and the impact of human activity.

White Birds Commonly Found Together

In many parts of the country, white birds tend to intermingle. I find this especially true with wading birds, which can make it difficult to decide who’s who. I’ve included the pictures below to help you see which birds are which when standing next to each other.

Great Egret Vs. White Ibis vs. Snowy Egret

Snowy Egret vs Immature Little Blue Heron

FAQ: White Birds

What are those white birds called?

Different types of white birds have different names. Check out this post for pictures and descriptions of common white birds.

How rare is it to see a white bird?

With many types of white birds in North America, it’s not too rare to see a white bird.

Takeaway

White birds abound across the continent. If you spot a white bird, hopefully, this quick guide can help you determine which one it is.